She quit her Amazon job to work with worm poop

"Composting with worms really quieted the corporate anxiety that has been part of my life for a very long time."

Before we get started today I wanted to boast about being featured in an issue of the excellent newsletter Un/well, in which Melanie Ehrenkranz explores both the cool and insidious sides of wellness (she’s covered how injectables like botox seem inescapable, bad skin days and the challenging topic of body talk). I’d recommend subscribing even if she didn’t give me a space to drawl about oatmeal and soap.

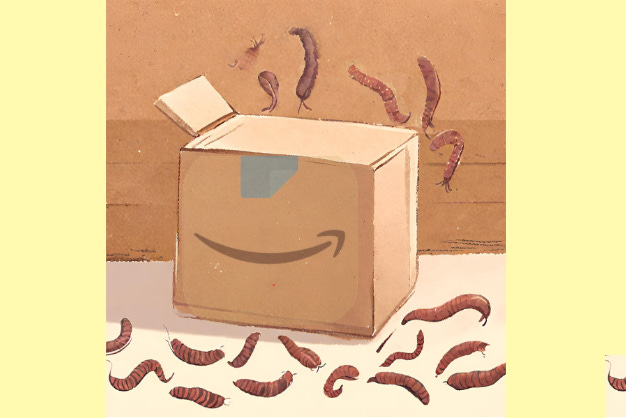

Going to jump right in here, cause I can’t wait any longer!!: I recently spoke with Lindsay Myers, a corporate content strategist-turned-worm-wrangler and I keep thinking about our conversation. I saw Lindsay’s post on LinkedIn, in which she announced she’d left her job at Amazon to focus on composting with worms, and I knew I had to talk to her. From the aforementioned post:

So here's the deal: I got into vermicomposting last spring. Every couple of weeks, I add heaps of shredded cardboard and leftover food scraps to some plastic bins, and hundreds of worms help turn it into fertilizer. It's fascinating. It's a beautifully sustainable system to mitigate food waste and it's as real as it gets. I was unexpectedly GRIPPED by this process and after talking about it all summer to anyone who would listen and joking about leaving Amazon to sell worm poop, I eventually realized that it, uh, wasn't really a joke anymore. Turns out, vermiculture lines up nicely with my goals and values, and there's more of an audience for compost content than I expected. Teaching people about this as I learn and experiment is already so much fun.

Lindsay first got into vermicomposting when her dad gifted her a 70-pound bag of worms, their poop and dirt for her garden (she accidentally left the materials in her trunk and still sometimes finds “worm jerky” in her vehicle. For this to happen and for her to still be beautifully passionate about worm composting tells you some important things about Lindsay.)

She’s still working out what she’ll make of this new focus, but most importantly, she wants to spread the word about worms. What does that look like? Maybe it’s creating content around worm compost (she’s really funny), hosting workshops, writing a children’s book or turning some combination of it all into something she’s yet to dream. She seems to be enjoying the journey of figuring it out 👏.

Our conversation below [edited and condensed for clarity blah blah] is a bit of a melange: You’ll learn about Lindsay’s passion for composting and existing offline, and also see the inner workings of the decision to quit something that failed to meet her values. I’m so inspired by her sense of self and community, and she makes me feel hopeful.

OK, so what is worm composting?

Worm composting — or vermicomposting — is the practice of feeding a mixture of nitrogens and carbon to composting worms. These worms eat the microbes that break down decaying food. They consume the decaying produce, like rotting spinach, whatever you put in there, and turn it into this incredible soil fertilizer byproduct.

It’s worm poop. People call it worm castings or vermicast. Vermicompost is the term for the finished product that has gone through the worms, it still has all kinds of good microbes and other stuff in there. And then you can use it on your garden; you can mix it into soil as a soil amendment.

You can mix it with water and turn it into compost tea [not for drinking], which can be another really good way of fertilizing your plants. It's fantastic.

It takes a couple of months to get a really nice finished product from setting up the compost bin to being able to use it in the garden. But I like that because it's not something that you have to constantly turnover and process and deal with [unlike hot compost]. You can just sort of put the food in there, let them eat, and then you have something you can use later.

I should preface this: I am not a scientist. I don't know. I studied ancient Greek, like, I am just barely learning the carbon, nitrogen, whatever. I think that makes what I'm doing kind of cool because I want people to understand, you don't have to be a biology or chemistry wonk to do this and see it working.

This is life and nature in action. I love that perspective.

I just get so overwhelmed by how much lettuce we're just letting go slimy. And when I think about the resources needed to produce that, the people who did it, the money we spent on it, and then the consequences of it going to the landfill, I have this thousand yard stare of despair.

On learning about — and falling for — worms

I read a little book called, “Worms Eat My Garbage.” It was more approachable. It sort of looks like a little graphic novel/comic book. It's got little drawings in it and it gives you the basics of what you need to get started and why you should do this in the home.

The other element of this that wasn't really clicking for me until I started doing it was how much food [the worms] can eat and how much food waste they can save. Because that's the kind of thing that keeps me up at night. I just get so overwhelmed by how much lettuce we're just letting go slimy. And when I think about the resources needed to produce that, the people who did it, the money we spent on it, and then the consequences of it going to the landfill, I have this thousand yard stare of despair.

I think about how I want to be in the world and in my community and just even in my household. I want to know what's happening to the things that I have consumed in some capacity or decided not to consume.

On quieting her corporate anxiety and pushing back on corporate nonsense

I was finding [being offline] was bringing me a lot of peace as I was learning how to do worm composting, figuring out when they're healthy and when they're hungry and what to do when it's too hot and how to better prep the food for them.

You know, troubleshooting things. I think that's really fun. And I like to say, there's no such thing as a worm emergency. In the very physical experience of going out there, separating the worms from the castings, touching them, like, how often do you play with bugs outside?

It really quieted the corporate anxiety that has been part of my life for a very long time. [Amazon was] starting to call for a return to office. It didn't make sense to me because most of my team was on the opposite coast or in other countries.

I would still be driving 14 miles one way to go sit on video calls, and then go back home. I calculated, if I was only going three days a week, I would still be driving almost 90 miles a week, which is nuts. So pointless! Like, this works fine. It had been running for three and a half years [in a remote capacity].

And it's not like I was missing deadlines or not communicating. But, you know, no one's thinking about one content strategist when they're making the corporate decisions. They weren't thinking about any employees in making the decisions. So, that tension was really kind of building, and I kept joking, like, “Well, you know what?If it doesn't work out on Amazon, I'll just give up and sell worm poop.”

I'm 34 and have no idea where the world is going right now, and I just don't want to sit around and passively find out if I could instead be making a smidge of a difference myself.

How the pipe dream became a reality

It was a buildup of the tension. The burnout was real. I was working on a project for six months. I was the only writer on it. I had, you know, approvals chain of like 20 people, multiple languages. Just. Wild. [Indeed, this is one of the most hideous experiences a writer can endure.]

And I'm like, man, I think I really need to be paying attention to my values a little bit differently. I'm sick of sitting at a desk. I want to be outside. I want to manage my own schedule again. And I had freelanced before for a couple of years. So the idea of going out to do my own business again was kind of daunting, but I knew I could do it.

Despite the fact that I'd spent months thinking about how much fun I was having with the composting, I was nervous to tell people what I was doing at first. I thought "I don't want to work here anymore" wasn't a good enough reason to leave if I didn't have another job-job lined up or a properly established business. From the outside I feel like that always looks impulsive and like, "Wow, yikes, hope they're gonna be okay..." or it leads to speculation about what someone's really doing.

So I was all coy about it, saying I was going to do some passion projects and community environmental work (which was also true). I guess that felt more legitimate?

But as I got closer to leaving, I was of two minds:

If I'm serious about spreading the word about worm composting because I love it and believe in its benefits, why not start by telling my coworkers?

I want people to see someone leaving Amazon, specifically, to do something more out there, tangible and values-driven — even if it's weird. I want people to see that if you don't feel connected to your work, if you don't like the decisions being made for you by a corporate entity, and your attempts to speak up and push back are going nowhere, you can leave.

I met great people and had some genuinely great times, but the longer you stay at Amazon, the more it gets into your head. The culture implicitly and explicitly says that whatever you're working on needs to be the most important thing in your life often at huge personal cost, and if it's not, you're not a leader or showing ownership.

It's this fabricated urgency that really demolishes people's sense of autonomy; the C-suite's messaging around return-to-office was blatantly "put up or shut up," very little nuance, and I was like NO! Wow! What the hell?! We don't have to just TAKE this! This shit is all made up! Obviously I'm pro working-from-home, but at its core this was all about agency to me.

Amazon could have laid me off at any time — and they'll find more content strategists. But I feel good about signaling, hey, the way you do things here is not okay with me and if I'm going to work this hard, I want it to be toward something I care more about on a day-to-day and existential level. I'm 34 and have no idea where the world is going right now, and I just don't want to sit around and passively find out if I could instead be making a smidge of a difference myself.

PSA: Anyone can compost with worms!

So this is just the scrappiest, quickest, dirtiest at-home worm bin I could possibly think of anyone doing. I cut a hole in the bottom [of the plastic container] and I have some drawer-liner kind of stuff [pressed to the bottom]. I just needed something that was a mesh that wasn't going to immediately break down.

I've got shredded paper from a shopping bag. The worms that I separated out and then there's like a, There's a manky persimmon in there, a banana peel, and I cut a hole in the top for ventilation, and I'm just going to see what happens with this.

And if you’re wondering: Does it smell?

It does not smell. If it's done right, you will get sort of like an earthy smell; I would compare it to fresh cut grass or walking in the forest, like that kind of mulchy smell if you've been digging around looking for mushrooms or something. If it's going the way it should be and the ratios of the greens and browns are correct, and the worms are healthy, you're not really going to get a smell.

Thanks to Lindsay for providing all of these wonderful worm photos. Be sure to check out her blog, subscribe to her newsletter, enjoy her Instagram and go crazy 4 worms!